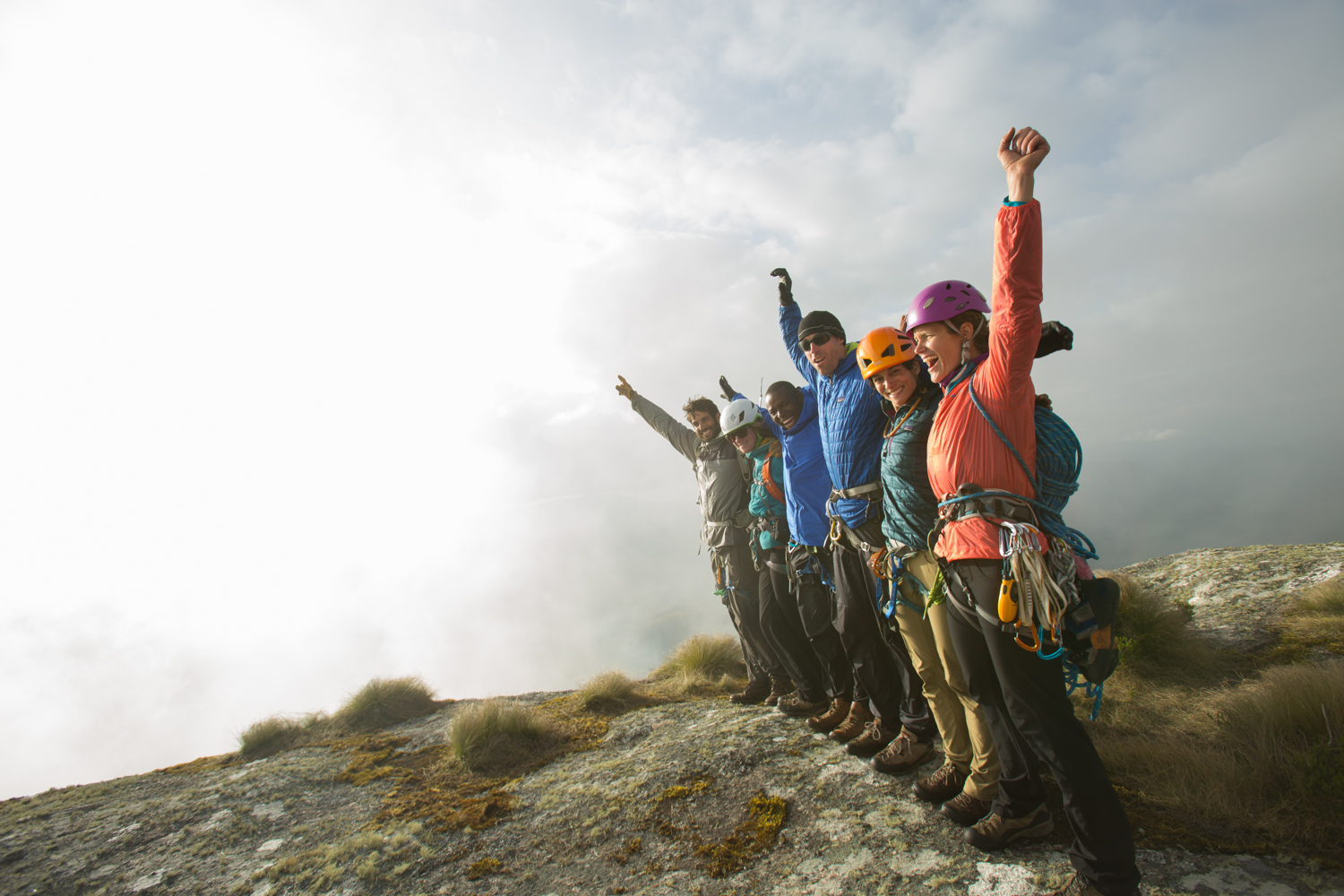

The Lost Mountain Climbing and Science teams celebrating success on the summit of Mt Namuli. Photo: James Q Martin.

In a former life I was a full-time climbing guide. That means I would normally know better than to introduce people to climbing for the first time on vegetated granite slabs interspersed with dirt and bush-choked chimneys. But the rules are different when you’re mission is a mash-up of scientific research, conservation action, and the establishment of the first technical climbing route up a mountain in Africa.

A blog in conjunction with Lost Mountain Sponsor Petzl.

This May, I led a team, including scientists Dr. Flavia Esteves (California Academy of Sciences, USA) Harith Farooq (Lúrio University, Mozambique) and Caswell Munyai (University of Venda, South Africa) up the 2,000-foot southeast face of Mt. Namuli, in Mozambique, as part of the Lost Mountain Project. The objective was to access, via the vertical granite that forms the Namuli massif, never-before-sampled hanging forests and vegetation pockets in search of new species of ants, beetles, spiders, skinks, snakes, and more. I was not a scientist; our scientists were not climbers. Good thing we had each other.

Kate Rutherford setting off on pitch four of Majka and Kate’s Science Project (IV 5.10-), Mt. Namuli, Mozambique. Photo: James Q Martin

To get the scientists and our film and support team up into the vertical, my climbing partner Kate Rutherford and I employed every technique and technical set-up in our arsenal. We taught the scientists how to climb to increase efficiency on lower-angle terrain. We fixed lines to the bottom half of our 12-pitch route and taught the team to ascend and descend ropes, allowing them independent access for specimen collection.

Harith, our herpetologist, climbed with his snake hook. Flavia and Caswell, both entomologists, climbed with dozens of pre-filled vials of ethanol, blow tubes, and microscopes for the ants. In the end, we chose a line that threaded up the sedge-covered face, linking scientific points of interest with beautiful, albeit run out, slab climbing. At one point, we had 16 people dotting Mt. Namuli’s southeast face.

Light and fast is the trend in modern climbing, but light and fast was not our objective on this trip. Instead we were focused on scientifically relevant and culturally impactful. It took more gear. It took more people. It took faith in a collective vision formed from the passions of many. And in the end, we did it: the scientists left with over 3,000 ants and 27 different herpetological species; Kate and I have a new route on Mt. Namuli under our belts; and our conservation team completed the first ever conservation study of the Namuli region, quite literally putting this unique mountain on the map for conservation action.

Stay tuned for The Lost Mountain film, coming in 2015.